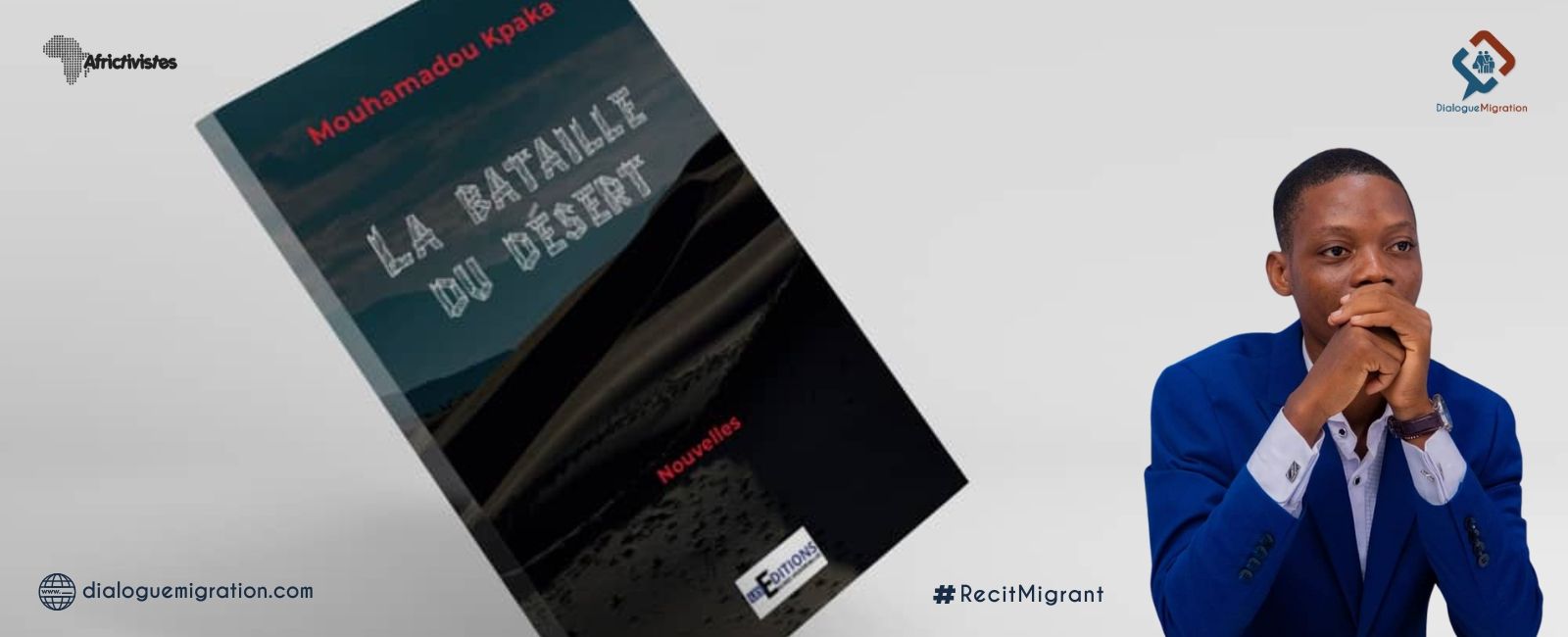

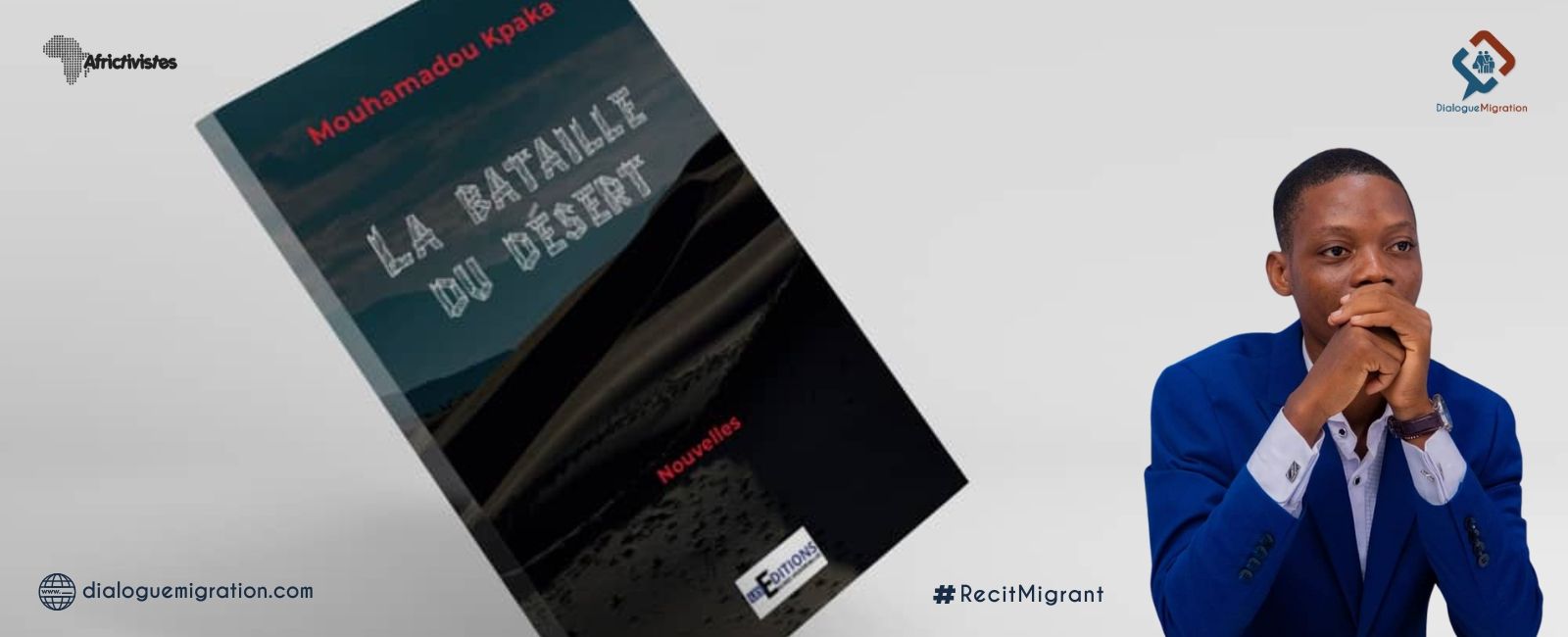

Aged 24, Mouhamadou Kpaka is a young Beninese writer, author of a collection of five short stories entitled The Battle of the Desert – La Bataille du Désert, published in February 2023 by Editions Encres Universelles in Cotonou, Benin. He tells Dialogue Migration about social realities, his queries on contemporary issues and reveals motivation behind his reflections scripted in his book, as well as the experiences that shaped his personality and his positions. Far from clichés, and other stereotypes, Mouhamadou Kpaka describes the experience of these fellows and existential conditions, which most of the time offer young people no other choice than to go elsewhere.

Who is the author of The Battle of the Desert?

I am Mouhamadou Kpaka, a writer. I hold a degree in SVT (Life and Earth Sciences, editor’s note), passionate about literature and everything that reflects beauty, this is probably what pushed me to publish my book The Battle of the Desert. I am also an environmental activist. I campaign for the protection of the environment and am very attached to issues of freedom.

What do you talk about in your book?

The Battle of the Desert is a collection of five short stories that report themes related to contemporary Africa, including illegal migration, endemic unemployment, the resurgence of coups d’état and many other evils. I also touched on Pan-Africanism, without forgetting to magnify Black beauty.

Why did you choose to address these themes?

Addressing these themes was somewhat prompted first by my pan-Africanist vision, also my vision of seeing everyone flourish in everything they do. You know, just because you’re a carpenter doesn’t mean you can’t afford a nice house, a nice car, and live easily. Just because you’re a farmer or a peasant doesn’t mean you can’t afford these things. But in Benin and Africa in general, what do we see? When you specialise in some professions, you are automatically condemned to live precariously. I see that the wealthy, those who are free from need, are for the most part those who make careers in politics and who occupy juicy positions in the state apparatus. It shouldn’t be that way. It is all these facts that pushed me to address these topics.

With my little experience, at the end of my bachelor’s degree in 2021, I had to get the Master’s degree before teaching. Did my parents and I have the means to enroll in a Master’s degree? If there were no other possibilities, maybe I’d travel for a better life elsewhere with all the risks that it entails.

In your book, you talk about the Sahel, why?

In the Sahel, there is terrorism, I have not been there, but the echoes have reached me. My reading is that after the Sahara, what will happen to the Littoral? Because after the hinterland countries we have the Gulf countries (Benin, editor’s note). We sit idly by and watch others go crazy. With their advances towards the coast, what will happen to us? It is this question that led me to talk about terrorism in the short story The Battle of the Desert.

You also talked about migration, what led you to address this theme?

I was touched by the story of a gentleman called Eduard, who spent the last fifteen years of his life in Nigeria. He worked in his village as a palm wine extractor. He did the extraction and processed it into Sodabi (local alcohol). Someone came from Nigeria and told him, “Where I left, they are looking for able-bodied arms, manpower to take care of the tasks; I believe that by going there you will make a fortune, you will have money.” The offer was too tempting, he did not think twice, given the precariousness that prevailed in his village, in Agbangnizoun in the department of Zou in southern Benin. He didn’t think twice before embarking on this adventure. In Nigeria, he realized that this was not what he was promised. But there he must be kept in captivity, working on a farm, from morning to evening without rest. He stayed there for fifteen years before finding a way to escape with some companions, since he was not the only Beninese in this condition on this farm. According to him, there were people from various backgrounds, Beninese, Togolese and others from the West African region. They lived in the same conditions in a form of arranged slavery. He wanted to go home when he came by our house to ask for help from my parents who gave him the little they could. It was at this moment that he told them the conditions of his departure from Benin and Nigeria. We are in the commune of Abomey-Calavi, Benin. He has already covered a very good distance before falling on us… In a way, it was his story that motivated me to address the theme of immigration.

Also, you talked about “Visa Express” in another short story…

It is also migration, and it was necessary to find a motive from Tchiké, the central character, of the new “Visa Express”.

From your position as a writer, what is your appreciation of these games and other immigration processes including Visa Lottery, Access Canada, Campus France and others?

I am a dreamer, a great dreamer. I want an Africa where the standard of living is the same as in Europe or America. But how do you get there? Can we really do it under these conditions? First of all, it must be said that we are terribly lacking in technical skills. I understand that universities do not really train properly. They do with the means at their disposal. How do you expect us to have renowned biologists, talented geneticists? Moreover, the vast majority of our teachers have received part of their training in the West. So regarding Visa Lottery, Access Canada, Campus France, I agree. First of all, I will clarify that I am not against immigration when it is carried out under the required conditions, legal and regulatory. Because you see, much of Africa has been closed in on itself for centuries. Millennia I would say. Someone has even argued that this withdrawal of Africa into itself has cost it a lot, including slavery and colonization. I believe that we have a duty today as young Africans to seek knowledge wherever it happens. Whether in the West or elsewhere. We will have to mute our pride, and seek this knowledge, because we need it to develop our countries.

And what about the brain drain, especially those who no longer return?

This is where the problem lies; this is the evil in reality. And the fault does not lie with the emigrant, but rather with the State, which has not really been able to regulate the conditions of his departure. When we observe well, those who go and do not come back are not always those who go with their own means; they are the scholarship holders. Those whose departure the state even finances. He leaves them there, and then that’s it. It is because he is aware that by coming back here he cannot give them the right conditions so that they can exercise what they have learned. So there is this obvious responsibility of the state itself. I would even say it is irresponsible not to create the right conditions for the employability of the talents we send to train.

So what are your perceptions on the issue of migration in Africa?

I think it is a good idea to give a brief overview of the situation, including the causes that motivate them. Because there are people who have no choice but to look elsewhere. I was browsing a social network last time and I came across an agency that offers to support candidates on putting together documents to migrate to Germany. The agency said that it is no longer worth taking the risk of dying in the Mediterranean when there is this possibility there that can easily be opt for and travel peacefully. In the comments, one of the Internet users said that he had already explored various offers and that it had not worked, and that then he wanted to take off, to risk crossing the desert and the Mediterranean. And that ‘what is he experiencing in his country that is not already equal to death, and that will discourage him from taking this risk?’ You see? That touched me a lot. If we do not attack evil at its roots, we will never be able to defeat it. Our States make democratic commitments, they say that they will respect each other’s freedoms, but in reality, they are missing out. Whether in Benin or elsewhere, there are frustrations, repression sometimes bloody. There are unemployed, there are workers who migrate and go on adventures because they do not have a job. If we can address these questions in a practical way, we can overcome the issue of migration. My perception is that I do not condemn migration. If someone wants to migrate, go to seek a better future elsewhere. We have all migrated. Homo sapiens migrated; otherwise the whole of humanity would be concentrated in Africa. It is migration that has repopulated the world. So if someone is planning to migrate, I will just advise him to take the formal, legal channels and that he does not go wandering and being mistreated by others before claiming happiness.

In March 2023, a racist fever gripped Tunisia following anti-migrant statements by President Kaïs Saïed on February 21, 2023 calling for an end to the sub-Saharan “hordes of illegal migrants” present in his country. What do you think of that?

Addressing this question gets me heated. I am very crude when it comes to these issues. Black Africa, that is to say the Africa of the tropics must realize that the Maghreb is not a friend. This is the case of Tunisia that we are currently experiencing. I don’t know what will happen to Algeria? Morocco is a bit integrationist… After Tunisia, there are Algeria, Egypt and Libya that make life very hard for Black people. It is the responsibility of our African brothers and sisters to know how to guide the path of their departure. What we have seen is evidence of the failure of our organizations on a regional or continental scale. The African Union waited a few days or even a week before issuing a mock denunciation. It denounced the fact but did not condemn it. The fact that one country is driving out the nationals of another country is a blameworthy and reprehensible act. I even expected that a procedure would be initiated for Tunisia’s withdrawal from the African Union. Listening even to the authorities of the country, they say “I am friends with Africans, my family married Africans”, it is as if they are not Africans. So there are these parameters that our organizations must take into account and crack down. That is, to pass laws, which unfortunately is not done.

You seemed determined, what is the meaning of your commitment?

Maybe what motivates me is my way of seeing things. We all have the right to a comfortable life. Whether you are president, peasant, minister or craftsman, we all have the right to a better life. But what is being done to ensure that every layer of the population has access to this well-being? For my part, I do not see anything connected. It seems that there is an already established order, a reserved caste that must be accessed before claiming happiness. This should not be the case. There are all these facts that revolt me. There is injustice and it must be said that it is chronic and flagrant in our African societies. I will not go into detail, but everyone knows that. Everyone knows that we live in a society where everything is trivialized, and social justice is relegated to the last rank. While it should be the hobbyhorse of the rulers. A society where justice is not the order of the day is a society already doomed to failure. Everything you build today, there will be frustrated people tomorrow who will destroy them.

Isn’t your commitment also limited to the first authors you discovered? Which ones have you read, or thinkers, inspire you?

I read Jean Pliya a lot and when you read him, you see that he is fed up, and that he has to fill the lines of his books to pour out. His seminal work “Les tresseurs de corde” is a requiem, a condemnation of the one-party system in Africa in the eighties. There is also an American author, Jack London, who is a socialist by conviction, a very committed author who has decried the excesses of inhuman capitalism, and glorified socialism, and preached the well-being of all. So there are these authors whose works have influenced me a lot.

Also, it must be said that I read a lot of African authors like Sembene Ousmane, Cheikh Anta Diop who is my ideological reference, Aimé Césaire, Victor Hugo and also some French authors, including Alexandre Dumas. In Benin, I read a lot of Florent Couao-Zotti, I started by reading Félix Couchoro, and young authors, like Alphonse Montcho, Théophile Sèwadé, Daté Atavito Barnabé-Akayi. Finally, I read a bit everything I lay my hands on.

Mouhamadou Kpaka, what are your perspectives?

Currently it is to succeed in getting readers to adopt this collection. My ambition is that this book be read and criticized within the reach of what is there. After that there are other writing projects that will come to life I do not know when. On my commitment, if one day I write essays, it would probably be on Pan-Africanism, the obliteration of democracy and others. Already, “The Battle of the Desert”, which is a collection of short stories, addresses the issues of our daily lives, perhaps not as people would have wanted, but in my own way.